Understanding Objective vs. Subjective Storylines

by Robert Tobin - Surf City Films

Screenwriting Lesson, 4 pages

Viewed by: 38 Residents and 3587 Guests

Lesson Screenwriting ABCs The Biz

We hope you enjoy the article!

If you are a screenwriter looking to network, learn more about the craft or get feedback and exposure for your own projects,

Click Here to become a Talentville Resident and join our growing community of screenwriters and Industry professionals.

OBJECTIVE VERSUS SUBJECTIVE STORYLINES

By

Rob Tobin

Okay, so you have a bunch of techniques with which to get the creative juices flowing. You also have a knowledge of the main elements of a well-told story, the HALF JOE mentioned in the last article. I’m going to go back to those elements again and again in the articles to come, because the relationships between those elements are as important as the elements themselves, just as the relationship between the elements of a car are as important as the elements themselves. You can have an engine, transmission, axles, wheels and drive shaft, for instance, but unless they are actually in proper relationship to each other, they’ll be useless in moving your car. Imagine an engine revving at top speed, but not actually attached to the drive shaft, or the drive shaft turning like a mo-fo but not attached to the axles.

The elements of a story are like that, so we’ll come back to them again and again in the process of establishing what kind of relationships you need between those elements.

So let’s talk about storylines.

The term storyline appears a lot in the film industry, often used to label different parallel storylines that occur, often in television shows, where perhaps one or more of the characters are involved in one plot or subplot, while one or more of the characters are involved in another subplot. So for example, on a medical drama, one doctor may be trying to save a patient’s life, while another doctor may be dealing with a personal situation or with another patient. “Grey’s Anatomy” is a perfect example where often one doctor may be dealing with marital issues while another doctor is trying to figure out how to most effectively operate on a patient’s brain tumor, while two more doctors may be trying to find an empty room in which to have sex. The number of storylines in that sense can be nearly endless, limited only by the length of the episode and the number or characters.

What I’m talking about, however, are two very specific types of storylines: objective versus subjective storylines. These are crucial elements of a story, in addition to and at least equal to the seven elements we previously mentioned.

The objective storyline is the storyline that takes place outside the hero, in the physical world that involves physical as opposed to moral or emotional victory. For example, let’s say we’re writing the story of an athlete struggling to come back from a traumatic brain injury. The physical victory might be anything from simply walking and talking again, to actually competing in his or her sport. So all of the goals and obstacles are physical in nature, and tend to be gross, easily seen, easily comprehended. They may not be easy to overcome, however, though they are probably simple even if not easy: strengthen the muscles, practice the skill, and maintain the discipline.

The subjective storyline takes place more on a personal and emotional level than strictly a physical one. It often involves overcoming the hero’s flaw and is usually a prerequisite to the hero being victorious on the physical level.

Let me give you an example. Let’s go back to the story of the athlete who has a serious accident, which causes traumatic brain injury. Let’s say the guy’s a football hero and a head-on-head tackle caused the injury. Physically, on the objective level, the goal and the process are simple even if not easy: rehab to the point at which he walks, talks, and/or plays again, depending on what the physical goal is. So the objective level is about overcoming physical obstacles to achieve a physical goal.

The subjective level will deal with overcoming a personal obstacle (the hero’s flaw) in order to achieve a personal goal. So let’s just make this up here: the football-playing hero is in despair after the accident and has given up. Everyone around him is trying to help him, the physical therapists and doctors and nurses are all doing their best to help him regain the highest level of health and ability he can. But he does not respond well because his despair leads him to give up too easily or perhaps even not to try in the first place. So on the subjective level, the goal is to overcome his flaw, which is despair, and the goal is to be able to give his recovery the best effort he can and to start living his life more fully.

Now, notice the relationship between the objective and subjective storylines: the objective storyline ain’t happenin’ without the hero first winning on the subjective level. That is usually the model in most screenplays – not all of them. There are a lot of different models, some of them so far removed from this traditional model that you wouldn’t recognize them. But if there is a traditional, “standard” storytelling model, it includes the objective versus subjective storylines (with some exceptions which I’ll mention below), and it involves the two storylines being intertwined.

So let’s say that the hero finds the motivation and skills with which to overcome his flaw of despair on the subjective level, and in the subjective storyline. He is not able to give it his all on the objective level of rehabilitation and training and may now be able to achieve his physical goal, as long as his goal is actually attainable. A hero who has his legs cut off may not be competing in the hundred-meter dash in the Olympics – or maybe he will, given that a double amputee, Oscar Pistorius, actually did compete as a runner in 400-meter race in the last Olympics. But someone who is a quadriplegic probably isn’t.

Now not all stories have this objective versus subjective story structure, and I’ll get into that in a second. But having both structures in a story increases the depth and sophistication of a story and also tends to strengthen characters, because the subjective level delves into who the character is, his or her main flaw, perhaps the reason she has the flaw, and what is necessary to help the hero overcome the flaw.

You can have both storylines and still have only one set of characters. By that I mean the opponent on the objective level can be the opponent on the subjective level as well. The objective ally can also be the subjective ally. Alternatively, you can double up: have an objective opponent and a subjective opponent; an objective ally and a subjective ally.

The reason you sometimes do this is that it is not always believable, for example, that the ally who is qualified to help the hero on the objective level is capable of helping the hero on the subjective level, since those two levels are often quite different. A guy who can help you become a better athlete or win a physical battle may not be the best person to help you with deep-seated personal problems.

Here’s a hypothetical example. Let’s say that the hero is successful and talented concert pianist. She has an accident that leaves her without the use of her hands.

Physically, she may want to try to regain the use of her hands so she can play again. Or it may take the form of her learning to play with her feet if her hands are not repairable. Whatever, the goal remains the same: to play the piano again. There is a strictly physical component to this story: the physical ability to play the piano.

There is also a personal component. If the hero is a young person to whom physical attractiveness is a key component to romance, for example, and/or a feeling of selfworth, there is also a very personal component. If she feels she is no longer attractive and worthwhile as a person, she may not have the emotional strength and inspiration needed to do the physical things needed to resume playing piano. She may not even have the courage to appear in public with her amputated or otherwise damaged hands, and appearing in public is a key component to being concert pianist.

So in order for her to have any chance to succeed in becoming once again a concert pianist, she has to perform certain physical tasks. Tasks she does not have the emotional strength to perform because of the emotional trauma caused by losing her hands.

So let’s say on the physical or objective level, the opponent is her is the person who runs a music competition she needs to win or at least do well in for people to take her seriously once more as a pianist. The ally may be her music teacher or maybe even a former music teacher who she abandoned on her way to the top. Now he is the only one who has the skills and the knowledge of her personally to help her physically be able to resume playing piano after the accident that took away the use of her hands. The fact that she earlier abandoned him may add a nice bit of conflict to the story.

That’s the physical level. But we already know that she is so handicapped emotionally by the accident, that she sinks into deep despair and bitterness, which will prevent her from even starting the physical process of rehabilitation and musical practice. So let’s create an emotional opponent: her mother, who was a stage parent who used the hero to live her own dreams vicariously and now, mortified by her daughter’s condition and ashamed of her handicap, represents exactly the kind of disapproval the hero feared. Until the hero is able to defeat her mother and overcome her mother’s disapproval, she will not have the will to triumph on the physical level.

Okay, so let’s create a subjective ally for this hypothetical hero of ours. Let’s make it her sister. Let’s say the hero’s sister was also the victim of their abusive mother’s negative attitudes and exploitation. Maybe the sister herself had been a pianist, had collapsed emotionally under her mother’s abuse and unrealistic expectations, and had quit music. She might be the perfect person to come to her sister’s aid and help her overcome their mother’s disapproval, because she understands it better than anyone in the world.

So you see, you can have two sets of characters, one for the objective level and one for the subjective level.

You can also take the very same story and use one set of characters for both levels. So let’s say the hero’s sister, having been a brilliant musician herself, is the one who not only helps her emotionally, but becomes her musical coach, so that she is the ally on both the objective and subjective level and it becomes a kind of platonic love story between two sisters, and there may be emotional blocks for both of them to overcome, perhaps jealousy by the ally over the hero having been the one to achieve glory, tempered by the hero’s accident and the mother turning on the hero the way she turned on the sister, so that now the two sisters are united against the mother, and maybe the sister also finds herself once again practicing the music that she abandoned so that both sisters triumph in the end both objectively by succeeding at music and subjectively by overcoming their mother’s abuse.

Now let’s say that the mother was also a musician and coached the hero. When the hero has the accident, the mother objectively stands in her way by refusing to coach her, as well as subjectively by being abusive and disapproving. With that simple change, you’ve created a single cast of characters that can work on both objective and subjective levels.

You can also have two lifechanging events, or one, it’s up to you.

Now, as mentioned, you can have a story that is all or at least mostly objective. An example would be an action movie where the action is the bulk of the film and there is little character development or theme, and the emphasis is on the physical goal, the physical obstacles and the physical accomplishments. There may be a token nod to the subjective, but in essence these are the kinds of movies in which a hero is challenged physically, and performs physical actions in order to triumph physically. Martial arts movies are often mostly if not completely on the objective level. The hero often has nothing but physical development to do in order to triumph. So, in its simplest form, a young man is beaten up by evil martial artists. He goes off and finds a martial arts teacher of his own, trains, starts to win fights, learns more, gaining physical mastery and learning more and more techniques until he is able to defeat the “bad guy” martial artists.

There’s nothing wrong with this kind of film, by the way. In fact, “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” one of the all-time great films, is in this category. Indiana Jones really doesn’t change personally or emotionally much during the course of the film. Rather he faces one physical challenge after another until he wins. Pretty much that simple. A more recent example is “The Avengers,” one of the most financially successful films of all time, and almost all on the objective level of action rather than emotional development.

The challenge in writing this kind of film is that the action has to be so good that it alone is satisfying to the audience. Another challenge is to keep such a film down in terms of budget, because the higher the budget for your script, the more difficult it becomes to fund it and thus the more difficult it is to find a producer for it.

The best films are usually the ones that combine a strong objective level with a strong subjective level. Those films do well at the box office and at the awards shows.

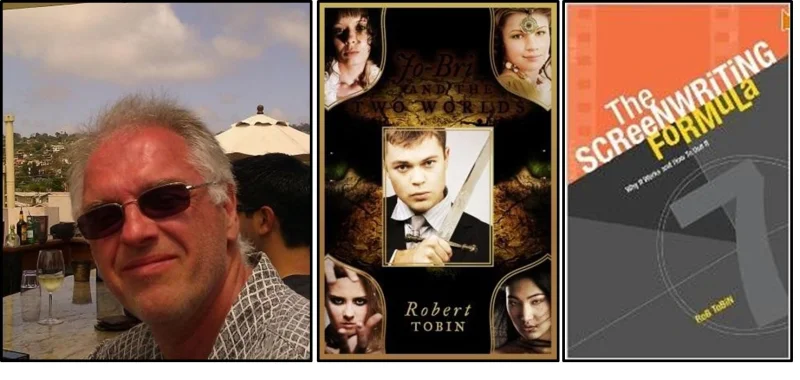

Rob Tobin is a produced screenwriter, published novelist ("Jo-Bri and the Two Worlds" and "God Wars: Living with Angels", available on Amazon.com and iBookshelf), author of two screenwriting books ("The Screenwriting Formula" and "How to Write High Structure, High Concept Movies" available on Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Google, bookstores, etc.), a former motion picture development executive and book editor, graduate of USC's prestigious Master of Professional Writing program, husband, father, Canadian, and he lives an extraordinarily happy life in Southern California. He is available for writing assignments at scripts@earthlink.net. Visit his website at robtobinwriting.com or surfcityfilms.net.

Robert Tobin - Surf City Films

Screenwriter • Script Consultant • Story Analyst • Producer

Rob Tobin

714-717-4289 • scripts@earthlink.net • robtobinwriting.com

RESUME

Screenwriting

• “Dam 999,” $10 million feature released by Warner Brothers, November 2011, shortlisted for 2012 Best Picture Academy Award.

• “Vengeance, ” $25 million feature in pre-production, fully funded.

• “Freedom Café,” in development with Cinigi Lighthouse.

• “Performing Love,” in development with Cinigi Lighthouse.

• “Camel Wars,” $40 million feature in development, Xoom Entertainment, John McTiernan attached to direct.

• “Better Than Human,” feature drama written for Living Earth Productions.

• “Across the Red Line,” sports action feature rewritten for the Cannell Studios.

• “Zen Cowboy,” feature comedy written for Triad Films.

• “Time for Joy,” sitcom pilot and one episode written for Riviera Entertainment.

• “I Love Ludo,” half-hour sitcom pilot, written for Bu West Productions.

• 21spec feature scripts completed, various genres

Books

• How to Write High Structure, High Concept Movies (Xlibris Press).

• Screenwriting: The Formula (Writers Digest Books).

• God Wars: Living With Angels, (Echelon Press, 2011).

• Jo-Bri and the Two Worlds, (Book Baby, 2012).

DVDs

• “The Seven Essential Elements of a Successful Screenplay” (Creative Screenwriting Magazine, produced 2005)

• “Credible Dialogue” (Creative Screenwriting Magazine, produced 2006)

Screenwriting Competitions

• Multiple Award winner, Written Word Award, Action on Film Festival (2011)

• Finalist, Los Angeles All Sports Film Festival (2011)

• Finalist, First Scene Screenwriting Competition (2011)

• Best Screenplay, Telluride Indiefest (2004)

• Semi-Finalist, Project Greenlight ((2004)

• Semi-Finalist, American Screenwriting Competition (2006)

Related Experience

• VP of Development, Interpreter Films & Management/Writers Boot Camp

• Director of Development, Motion Picture Division, The Cannell Studios

• Director of Development, Midnight Soldiers Productions

• Story Editor, Freddie Fields Productions

• Freelance script analyst, TriStar, Interscope, Spelling, Turner, HBO, Goldwyn, et al.

Education

• M.A. in Professional Writing, USC, Los Angeles, CA

• B.A. in Creative Writing, UVic, Victoria, Canada

Comments on Understanding Objective vs. Subjective Storylines