Screenwriting ABCs Script Formatting

Direction Writing Tips: Part 2

by T. J. Alex

Book Excerpt, 5 pages

Viewed by: 27 Residents and 174 Guests

Direction Writing Tips: Part 2

Avoid Redundancy:

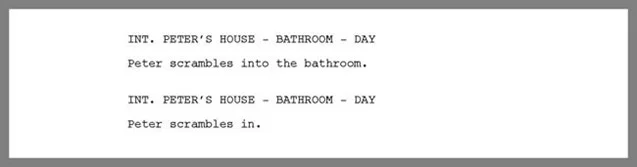

Sometimes when moving from a Scene Heading to a Direction paragraph, writers will repeat something already established in the Scene Heading. In the first example below, we know the scene will take place in the BATHROOM in Peter's house. We do not need to be told Peter enters the bathroom. Of course he does. The second example shows how to write it without redundancy.

Write Lean:

"Write lean" is a phrase often heard in screenplay circles and used by screenplay experts. It doesn't simply mean to write short, choppy, unimaginative sentences. It means to tell the story and move it along without adding a lot of uselessness that does nothing for the story.

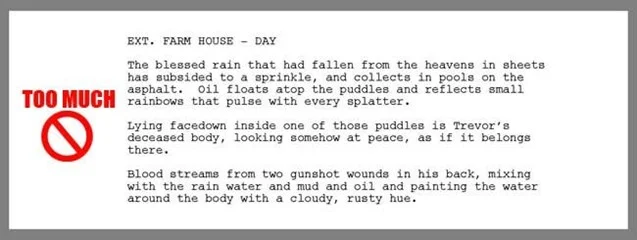

Look at the example below:

Who needs all that useless description? We aren't writing a novel here. This is a screenplay. If the information provided isn't essential to the story, then why is it there?

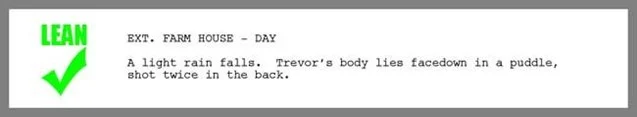

Let's look at the same scene set up, but with all the unnecessary information taken out:

That is really all the information we need for the action of the scene to progress.

That's writing lean.

Write Only What Is On Screen:

One mistake writer's make, which lends to their doing the opposite of writing lean, is adding information that will not appear on the screen.

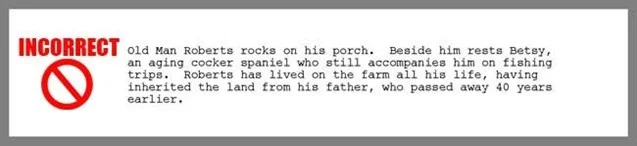

Look at this example:

There is a lot of useless information here that the director could not show on screen. The audience isn't going to know that the dog accompanies him on fishing trips. The audience isn't going to see that Old Man Roberts has lived on this farm his whole life, and he inherited the land from a father who has been gone for 40 years.

You might as well get rid of this pointless information, because it cannot be shown on screen.

Write ONLY what is SEEN and HEARD!

So, let's trim the fat, and write lean:

Much better!

But let's say the writer truly WANTS the audience to know more of the man's relationship with his cocker spaniel and/or how Old Man Roberts came to own the land...

Well, write it. Add flashbacks or let the information unfold slowly within the story. But the way it was written makes it impossible information for the director to show.

Dramatize the Dramatic:

Okay, writing lean does not always mean writing less. There are some exceptions to the rule.

Look at this example below:

Nothing wrong with that technically. I might advise stronger verbs, but the short paragraph sets the scene and gives all necessary information. If two characters were briefly separated and a few minutes later find one another, probably this will suffice.

However, what if the entire film is about these two characters finding one another? What if the hero's quest has been to be reunited with his beloved, and this scene is the culmination of all his efforts? This is the scene the audience has been waiting two hours for.

Then Dramatize the Dramatic!

Feel free to let your creative juices run wild (a little) and delve into the scene a little more to give the reader a sense of the scene's importance.

Here is the same scene with a little more Drama thrown in:

Well, that won't win any awards, but it is four short paragraphs that set the mood and emotion of the scene a little more than the previous example. The reader will be a more moved and feel the importance of the moment.

Now, a writer can overdo it. Some writers will write PAGES of colorful description to set up this all important scene. Don't. Dramatize the Dramatic . . . but don't go overboard. Even when you write drama, write lean.

Write Specific Words:

There is another time when writing more is okay.

Look at these examples:

Boring!

But not JUST because of the weak verbs. It would help if Peter "slides" into his car, but we could liven up the writing by being more specific as to the type of car he slides into.

Here are the same examples, but with more specifics:

Isn't that much better?

Yeah, sure, it isn't as lean, but that's okay. Because without loads of descriptive paragraphs, we've used a utility that allows us to say something of the character by being specific as to his preferences.

Had Eric "climbed" into a beat-up '57 Chevy truck, we'd have a different image of him. Had Arnold emerged from the bathroom donned in a tattered and dirty suit, and we described it as a "Goodwill special," we'd see Arnold in a different light.

Getting specific with objects related to a character means more words on the page, but it also does much to compliment the character and tell the audience something of his/her personality.

Don't get me wrong. I'm NOT telling you to describe every single piece of clothing a character is wearing every time he changes clothes. Get specific when doing so tells us something of the character, and do so quickly and efficiently.

Incomplete Sentences Are Okay:

Unlike novel writing, grammar rules do not always have to be followed when writing a screenplay.

Incomplete sentences not only help writers write lean, but when used correctly they can add tension to a scene.

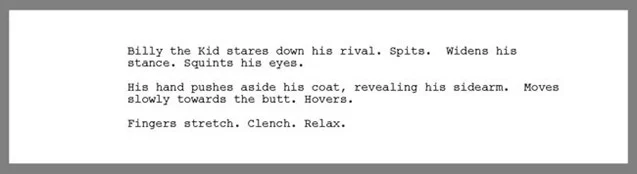

Take this example:

Many of the sentences above are only one word, and those are verbs. I set up the subject of the verb, then until the subject changes I don't repeat the subject.

So Billy the Kid stares, spits, widens, and squints in four sentences, but I only mention the subject (Billy the Kid) once.

In the next paragraph, "hand" pushes, moves, and hovers.

"Fingers" stretch, clench, and relax.

Once the subject is established, a writer can write incomplete sentences using verbs that modify the subject.

Notice, also, that the subjects in question get smaller every time. The first paragraph is dedicated to Billy the Kid himself and what he is doing. Next is his hand. Next his fingers.

This adds tension to a tense scene, keeping the reader (and eventually the audience) invested and on edge.

I'm also directing the camera without camera direction, but that's another lesson.

Using Similes and Metaphors:

Similes and Metaphors are great ways to describe a character, object, or location without overloading the page with useless description.

A Simile is a writing device that compares two seemingly incomparable things using "like" or "as" as a means to give the reader an image of the subject.

A Metaphor does the same thing, but rather than using "like" or "as" to make the comparison, instead draws a 1-to-1 comparison of two things by using a "to be" verb. 1-to-1 comparisons are one of the few times "to be" verbs work as good, healthy writing.

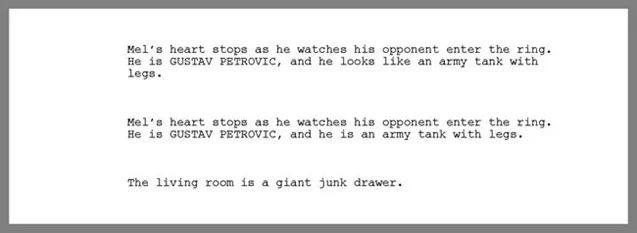

Here are some examples of Similes and Metaphors being put to use:

The first example above uses a Simile to draw a comparison between Gustav Petrovic and an army tank, two things that ordinarily would have nothing in common. But the comparison here draws a great image for the reader of what Gustav looks like without going into over-reaching and descriptive personal detail.

The second example takes the same scene, but uses a Metaphor instead of a Simile, saying that Gustav IS an army tank, rather than he is LIKE and army tank. Either way is fine, but I personally prefer a good Metaphor. Notice, Metaphors typically require fewer words, which makes for leaner writing.

The last example uses a Metaphor to give the reader an idea of what this particular living room looks like. I could have gone into great detail, describing the trash on the floor, piles of crap all over the place, and painted a long, drawn-out picture for the reader. But the simple Metaphor device used above does so much more with so much less.

By the way, "Less is more" is another common phrase heard in screenwriting circles. It is another way of saying, "Write lean."

Avoid Foul Language:

You would think this should be a no-brainer, but you'd be surprised. Foul language doesn't need to be used in Direction paragraphs. You can use it in Dialogue in order to be true to how a character actually speaks, but dropping the F-Bomb in Direction does nothing to move the story along.

Most producers or script readers might not be offended with a little colorful language, but some might. No reason to get your otherwise well-written, incredible story tossed in the garbage over a few four-letter words.

-------------------------------

For more screenplay formatting rules and advice, check out the book, Your CUT TO: Is Showing! by T. J. Alex or visit www.scripttoolbox.com. From there, please like the page on Facebook, and share it with your friends.

If you have any formatting questions, please email T. J. at tj@tjalex.com.