Creating Dynamic Scenes - The Opening Pages

We hope you enjoy the article below.

If you are a screenwriter looking to network, learn more about the craft or get feedback and exposure for your own projects,

click here to become a Talentville Resident and join our growing community of screenwriters and Industry professionals.

Article

Viewed by: 32 Residents and 665 Guests

Creating Dynamic Scenes

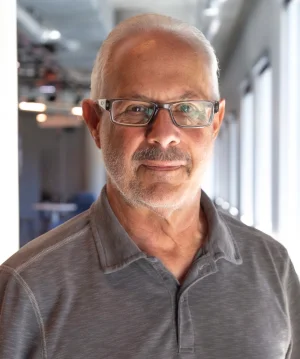

By Paul Chitlik

SETTING THE STAGE

Here’s today’s reminder that the most crucial element of a scene is conflict. Without it, a movie is just everyday life, not the 100 minutes condensation of life that we expect to see when we go to the multiplex. A movie is heightened reality. Every part of it is a distillation of real life, while still resembling real life.

Sequences consist of a group of scenes that are related in purpose and/or time. They also reflect the three act structure, so that while a scene can stand on its own, it can also have its function as part of a series of scenes.

Let’s talk about scenes in opening sequences.

SO GOOD THEY DID IT FOUR TIMES

No, it’s not what you think. I’m referring to Die Hard, screenplay by Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza, based on the novel by Roderick Thorp. The box office that Die Hard generated convinced Fox to sink money into a sequel, and they were well enough rewarded by that one to want to come up with a third and a fourth. Why? Action movies are a dime a dozen. Okay, $50 to $100 million a piece. (Or $250 million bombs like John Carter.) But most of the big ones make money based on the box office pull of their stars and/or amazing action. Fox didn’t have a big star in Willis at the time. He’d done tv and was popular enough, but he hadn’t established himself as an action star, just as a wisecracking romantic tv character – a long way from Schwarzenneger. What made this film big? We cared. And we cared enough to tell our friends to see it, and millions of them did. And when did we learn to care in a non-stop action film?

No, it’s not what you think. I’m referring to Die Hard, screenplay by Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza, based on the novel by Roderick Thorp. The box office that Die Hard generated convinced Fox to sink money into a sequel, and they were well enough rewarded by that one to want to come up with a third and a fourth. Why? Action movies are a dime a dozen. Okay, $50 to $100 million a piece. (Or $250 million bombs like John Carter.) But most of the big ones make money based on the box office pull of their stars and/or amazing action. Fox didn’t have a big star in Willis at the time. He’d done tv and was popular enough, but he hadn’t established himself as an action star, just as a wisecracking romantic tv character – a long way from Schwarzenneger. What made this film big? We cared. And we cared enough to tell our friends to see it, and millions of them did. And when did we learn to care in a non-stop action film?

In the first ten minutes.

If you’ve been hanging around the film business long enough, read any of the textbooks on writing, ever talked to a development executive, you know that the first ten pages of the script (roughly the first ten minutes of a film) are the most crucial for making up a reader’s (or viewer’s) mind. We have to learn who the film is about and what the film is about. We have to learn to like the protagonist (the hero) and understand what he wants. We have to learn about his world. And we have to learn what’s messing up that world. We need to learn about his humanity and his challenges. We have to invest in him almost immediately so that, in the case of action movies, the action becomes important enough.

You can have gratuitous action in a $3-5 million dollar made-for-foreign, one-star on the marquee flick, but for the film to really take off, for the money to roll in, for the sequel to be imminent, you need the action to matter. Just saving the world isn’t enough. Sure, James Bond does it; but he’s a special case, and don’t we know enough about him by now to care? Or, if we don’t, aren’t we carried along by the guy’s charisma, the Bond Girl’s body, and the gadgets?

So how do you get an audience to care in the first ten minutes without laying down a lot of expositional dialogue that sounds like it came out of the mouth of the maid in a drawing room comedy explaining to the audience just who everyone is and what they’re up to, so we’ll laugh when the mistress falls out of the closet? Let’s look at Die Hard and see what an opening sequence can and must do.

![]() The opening shot of the movie, over titles, is that of a jetliner landing at LAX. Nothing new there, just establishing. But almost immediately we meet John McCane, though we will not know his name for some time. We also don’t see his face immediately, just his hand gripping the armrest for dear life as the plane lands.

The opening shot of the movie, over titles, is that of a jetliner landing at LAX. Nothing new there, just establishing. But almost immediately we meet John McCane, though we will not know his name for some time. We also don’t see his face immediately, just his hand gripping the armrest for dear life as the plane lands.

This tells us something important about John – he either has a fear of flying or of heights or both. And that he is a human being, a hero with a flaw. We don’t even know yet who the hero of the movie is going to be (though we can guess since his is the first recognizable face), but we do know we can empathize with him because he’s not perfect. Characters without flaws are not as likeable as characters with them, and though it isn’t uncommon for an action hero to be practically flawless, the ones with imperfections are the ones we really root for.

Immediately the screenwriters begin to set up things that will pay off later in the movie. His seat neighbor counsels him on how to avoid jet lag: you just grasp the carpet with bare toes. And we find out that he’s been a NYPD cop for eleven years.

The opening scenes (sequence) serve to tell us about the central character and his current condition.

Then we switch scenes to set up his wife, the emotional relationship that John will have at stake in this story. We’re not exactly sure what the situation is – separation or divorce – but we know it isn’t good between them when she slams the picture of their family face down on the desk. We see, though, that she is a woman of some means and power: she’s got a nanny at home and a prestigious office at work.

Then we switch scenes to set up his wife, the emotional relationship that John will have at stake in this story. We’re not exactly sure what the situation is – separation or divorce – but we know it isn’t good between them when she slams the picture of their family face down on the desk. We see, though, that she is a woman of some means and power: she’s got a nanny at home and a prestigious office at work.

Then it’s back to John, whose name we learn from the sign a driver waiting at the gate is holding. So exposition is coming in bits and pieces. The driver asks some pointed questions, and John admits he’s married, that his wife moved out to LA six months ago for a job, and so on. The driver asks all the questions the audience wants to ask. We’re beginning to know Mr. J. McClane. We know the state of his marriage, his career, her career (though it’s vague as to what exactly she does), why he didn’t follow her to LA, and his attitudes. We also know he loves his kids (the big teddy bear). All this before the main titles are over.

Now the writers use Argyle, the limo driver, to help us understand what McClane’s goal is. He lays out a scenario for the reunion: “The lady sees you, you run into each other’s arms, and you live happily ever after.” McClane responds laconically, “I can live with that.” That’s what he wants. That’s his goal, his motivation for all that will come later. That, in addition to the freeing of the hostages, is what he must accomplish in this film.

The set-up continues with Argyle making him a deal to drive him to another location should the scenario not play out as hoped. This puts Argyle in the garage where he will make several other appearances throughout the film.

We’re still in the first ten minutes when McClane enters the Nakatomi Building and finds it quiet. He finds out at the front desk that his wife no longer uses her married name at work, so we learn something about her as well, something that will come back several times and pay off well in the end. It irks him that she uses her maiden name. More character development. We notice security cameras – they’ll pay off later. We learn about the party on the 30th floor and that there are no other inhabitants in the building. Now it’s time to hit the party.

Here is where the screenwriters, or possibly the director in editing, stumbles. A runner had begun in the airport with bemused comments on people that struck McClane as being “California.” He again comments when he’s kissed on the cheek by a male stranger. But this set up is never paid off. We expect it to be, but nothing ever happens, though it has followed two thirds of the rule of three. No matter, we soon forget about this when he’s met by his wife, Holly, and escorted into her office where her colleague is sniffing cocaine. Holly is emotional about the reunion, but controlled in front of her colleague.

So far, it could be any relationship movie. But when we see a large truck fill the screen and hear foreboding music, we know that the truck is going to be trouble for McClane and that his world is about to change.

Back on the relationship, Holly invites John to stay in the spare room, but the conversation soon turns into an argument, picking up where they, presumably, left off months ago. Soon after Holly is called away (again, business interrupts their relationship), the intruders take charge of the building, shutting down its systems and closing off its exits.

Meanwhile, John is barefoot in the bathroom grasping at the carpet with his toes as his seat neighbor on the plane had suggested. Set-up/pay-off number one. Later, this will be paid off further when he has to run through piles of broken glass in his bare feet. Pay-off number two: he’s on the phone with Argyle when he gets cut off. Then shots ring out, and we’re on our way, fully invested in the hero and his dual mission (because now we know he’s going to have to save his wife as well as his relationship with her). Now the violence, whoops! I mean action, has a larger purpose. While saving a group of hostages is a good and worthy purpose, if we don’t know them or the savior’s stake, we don’t really care enough to sit through a two hour movie. But if there’s a relationship hanging by a thread, if we know there’s a pregnant woman whom we’ve met (Holly’s assistant), then we give a damn. Setting up the characters and the situation, and getting us to care about what happens is the job of the first ten minutes. If it isn’t done then, we don’t usually read (or watch) past that.

As you can see, even in an action picture as intense as Die Hard, we watch primarily because we care about the characters. And we create the audience’s perception of our central characters in the opening sequences.

Let’s look at the first ten pages of His Girl Friday, screenplay by Charles Lederer from the play The Front Page by Ben Hecht & Charles MacArthur. You should be able to find it online. If not, view the video. In a normal screenplay format, the rule of thumb – often wildly inaccurate – is that one page equals one minute of screen time. In a Howard Hawks’ film, though, they talk way too fast for that to apply. If you’re viewing the video, we’re talking about the opening of the film until Burns leads Hildy out of the city room.

In the script, MacArthur gets us into the world immediately, and in the first page we hear the cynicism of an anonymous reporter. Seconds later, we meet Hildy Johnson, who’s first line of dialogue tells us she used to work there. She also tells us something about Burns immediately: “Tell me, is the lord of the universe in today?” Those few words expose her opinion of him. Soon, we have a good idea about Bruce, too, partly through dialogue and partly through actions like opening the gate to the city room. As we follow Hildy through the city room, we see she was a popular employee, then we find she’s divorced and about to see her ex-husband, the “lord of the universe.” Intriguing, isn’t it?

Then we’re introduced to Burns, about whom we already know quite a bit. Now we see it confirmed – the “lord of the universe” has a lackey helping him shave.

If you’ve answered the question “why him/her?” for your own character, you’re ready to ask “why now?” Why do we pick up these characters at this moment in time?

For Burns we immediately find out the “why now” question – there’s a crisis over a scheduled hanging. For Hildy, the “why now” is she’s about to get married, and she wants Burns to stop harassing her. In seconds we know what these two people want and what the conflict of the film is: he wants her back, she wants to get away from his influence. Or so she thinks.

We quickly see, too, the character of Bruce Baldwin in contrast with Burns. A detail as simple as the action of holding, or not holding, the swinging door out of the newsroom says loads about who these men are.

So, Hildy’s and Burns’ goals are opposed. And Bruce’s and Burns’ goals are opposed. The central conflict is established.

Opening sequences, composed of several (no set number) scenes have to be very specific as to purpose. They have to convey a lot of information in a very short time and in a very interesting way.

SHOW IT, DON’T TELL IT

This is one of the most famous dictums of film writing. Film is primarily a visual medium. The power is in the picture. Remember, they were silent for the first twenty-five years or so. The story always had to be told visually. And that still is the best way to communicate with a viewer (or even a reader, as paradoxical as that may seem). If you can show a character’s traits visually, in action, rather than have him/her tell us, you’ll make a stronger impression on the viewer.

Look at all the things we were shown in His Girl Friday – the way Hildy dressed, her relationship with her fiancé, her familiarity with the staff when she walked through the bullpen. When we first meet Burns, we learns loads about him, starting with the fact that the has a lackey helping him shave in the office. He truly is, or thinks he is, Lord of the Universe, to use Hildy’s words. Those same words had told us much about Hildy’s view of him; dialogue is important. Now we see it confirmed by his actions and attitude.

Whenever possible, then, show us that McCane is afraid of flying by writing about his knuckles going white as he grips the seat arm instead of having him tell someone it’s his first flight and he’s scared. Show us his wife is conflicted about the relationship by turning over his picture. Show us the difference between Hildy’s ex-husband and her future husband by how they deal with a swinging door.

One thing readers don’t want to see, though, is a long block of description on a page. They like white space. It makes it easier to read. It gives them the illusion that your script is a fast read. So, if you intend to have lots of action without dialogue, break it up into short paragraphs. Throw in a line of dialogue from time to time. Make it look soothing to the eyes.

Now, how do we plan an introductory, or any other, scene? Writers refer to the parts of a scene as beats. A beat is a single action described as minimally as possible. Let’s go back to the Romeo and Juliet scene in the first blog entry.

BEAT ONE: Romeo arrives home, angry.

BEAT TWO: Juliet watches a soap on TV.

BEAT THREE: Rome demands dinner.

BEAT FOUR: Juliet tells him to get it himself.

BEAT FIVE: Romeo threatens her. The baby cries.

BEAT SIX: Juliet slams it on the table.

BEAT SEVEN: Romeo, disgusted that it’s spaghetti again, sweeps it to the floor.

The scene has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It has action. It has dilogue. It’s ready to write.

Now, watch the first five minutes of any movie and see what you can learn from them about the character. Think about how you could apply that technique to your own writing. In your script, are you showing us who the character is, or are you telling us?

For more information, see Paul’s book, Rewrite, a Step-by-Step Guide to Strengthen Structure, Characters, and Drama in Your Screenplay, mwp.com. You can also get copies of his original The New Twilight Zone scripts from Digitalfabulists.com. Check out his website, Rewritementor.com, for info about Paul and his rewrite retreats and consults.

© Copyright 2012 by Paul Chitlik. Copying or dissemination in any format other than a single printout for personal use is prohibited.

Comments on Creating Dynamic Scenes - The Opening Pages